Is social media destroying democracy?

Originally submitted: June 2021

This essay was written in a time - seemingly long ago - when Dame Jacinda Ardern was our Prime Minister. She certainly was an invaluable example to have when studying the intersection of media and politics, due to her novel utilisation of social media.

Introduction

“Democracy involves making political information as accessible to as many people as possible, even as a by-product of other interests” (Kemp, 2016, p. 14). If this quote is anything to go by, then I believe social media is strengthening democracy, not destroying it. Thanks to social media we are able to engage in politics regardless of time, place or original intention.

Inspired by the above, I will research whether social media is making politics more accessible for the average New Zealander. I begin by proposing that the connectivity allowed by social media has increased the transparency and approachability of politics and politicians. Secondly, I argue that politics’ presence on social media makes it easier for younger generations to engage. On the other hand, I look at the proliferation of clickbait, misinformation and disinformation corrupting our political intake. Finally, I address the ability social media has given us to fall into echo chambers. In my conclusion I weigh up my findings.

More transparency and approachability

Political information has become accessible at any time and place, making it easier for people to engage with it. As put by Marshall McLuhan, “we now live in a ‘global village’” (1967, p. 63). Open networks such as Twitter are testament to that, as issues from anywhere in the world can become ‘trending’ and be brought to the attention of all users. Social media has redistributed the means of communication and information – no longer is the public sphere limited to the bourgeoisie (Lunt & Livingstone, 2013). As for politics, social media can be utilised to educate the public on a topic which is still seen as a domain of the bourgeoisie. This is happening in New Zealand via the Today in the House series in which Speaker Trevor Mallard informs viewers of the daily Parliament business. These short videos, posted across the New Zealand Parliament’s social media, are a quick and straight-forward way of engaging citizens with politics and promoting democracy, as many are unaware or sceptical of what goes on in Parliament.

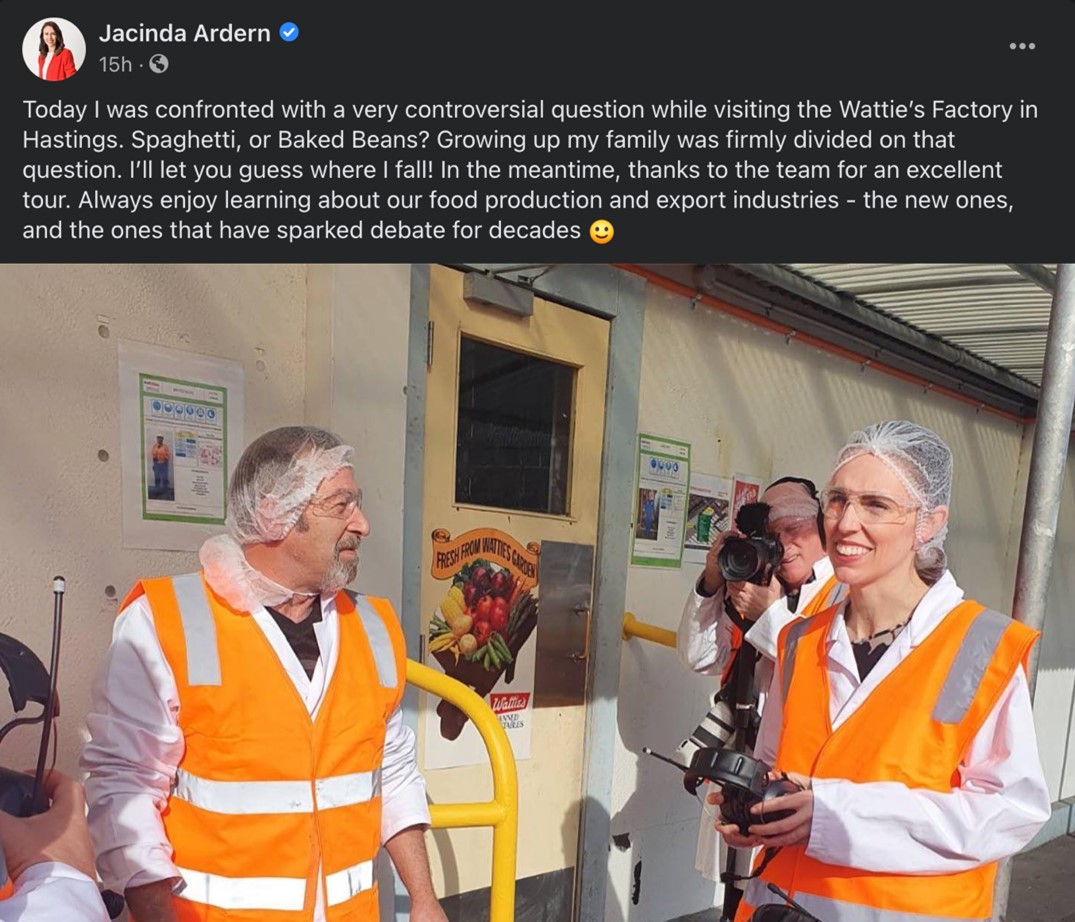

The aforementioned series is a wise move not just because it educates the public, but also because it aids Trevor Mallard’s reputation. Politicians who are active on social media, especially in video format, become more “human”, something which paradoxically elevates them to ‘celebrity politician’ status (Street, 2004, p. 439). There is no better example of this than Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern - as of June 11th 2021 her Facebook page has almost 1.9 million followers, while National Party leader Judith Collins’ has 71,000. When Thomas Meyer wrote “If democracy is nothing but legitimation by the most successful form of communication, then the communication artist is the best democrat”, Ardern was clearly the kind of “communication artist” he had in mind (2002, p. 79). Ardern uses social media to genuinely engage with followers through livestreams and regular updates complete with humour and emojis, as seen in Figure 1. This usage of social media allows politicians like Ardern to feel more approachable, thus encouraging a more representative public sphere. As mentioned earlier, the bourgeoisie are no longer gatekeepers of the public sphere – people can connect with politicians on social media directly and vice-versa, without journalists acting as the middleman. This not only helps to disassemble the “mediacracy”, but also to find a balance between “top-down” and “bottom-up” communication (Hayward & Rudd, 2006, p. 480).

Figure 1: An example of Ardern’s Facebook posts (Ardern, 2021)

My two previous points support the idea of ‘digital democracy’, which is defined as the use of digital tools “for purposes of enhancing political democracy or the participation of citizens in democratic communication” (Hacker & van Dijk, 2000, p. 1). What goes on in Parliament is no longer confined to those walls – aside from Mallard’s Today in the House, other initiatives include livestreaming of Parliament, online submissions on bills, and online petitions. Social media moves the ‘digital democracy’ concept closer to Jean Jacques Rousseau’s (1762) idea of ‘direct democracy’, as citizens share platforms with their representatives and gain the ability to collectively set the political agenda.

Politics for digital natives

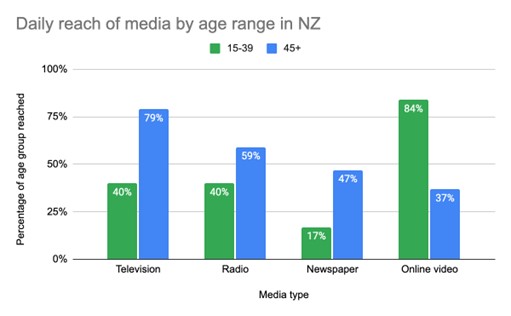

One need only look at the demographics of social media users to understand why social media is important for political communication. As shown in Figure 2, online video such as those on Facebook and YouTube reaches 84% of 15- to 39-year-olds daily. This is over double the reach of traditional media formats, whose main audience is the older generations. Politics needs to diversify and become more than just newspaper articles, 6pm news and talkback radio if it is to reach the youth - social media presence is the key.

Figure 2: Daily reach of media by age range in NZ (Glasshouse Consulting, 2020, p. 48)

Young people have learned to harness social media to draw attention to political issues, exercising their democratic rights in novel and effective ways. Social media has proved vital not just for educating youth, but for allowing them to participate in the public sphere and speak up regarding topics that may not otherwise be addressed by older people. An example of this is high school student Lilith Wiegand’s campaign for out-of-zone enrolment rights in co-educational schools for students who identify as transgender or non-binary (Stuff, 2021). Her petition, created via the New Zealand Parliament website, has been shared across Facebook, Twitter and other platforms by individuals and organisations like InsideOUT and Q Youth. Being in a digital format and getting promoted by those in the target demographic is likely to produce better results than a paper petition or newspaper feature could, as they are less accessible.

Commodification and corruption

Corporate power is commodifying politics, aiming to provide content that puts entertainment and fiction above education and truth. An example that follows us everywhere online, including on social media, is clickbait. Clickbait has infiltrated not just public forums like Facebook, but also more reputable online news sources, blurring the lines as articles and advertisements are presented in alarmingly similar ways. In fact, Stuff and the New Zealand Herald website have come under fire from the New Zealand Press Council for publishing paid content “that masquerades as news stories” (New Zealand Herald, 2017). If professional media outlets can stoop that low, the reliability of political news on social media is certainly worthy of scrutiny. The placement, appearance and proliferation of clickbait is just another form of agenda-setting, except this time it is profit which is top of the media’s agenda.

Though there are benefits to the ease of accessibility and participation afforded by social media, these features make it easier to manipulate content in comparison to traditional media sources. The prime dangers are disinformation and misinformation. While disinformation is defined as the intentional distribution of “inaccurate or manipulated” content, misinformation is the resulting spread of disinformation by people who believe it to be true (Weedon et al., 2017, p. 5). The ease of propagation of dis/misinformation on social media has generated fear due to its potential for weaponisation by populists. Open networks are the most susceptible by design; add the paid ‘trolls’ and bots utilised by many populist groups, and dis/misinformation is impossible to avoid (Deb et al., 2017). However, other networks like Facebook are not immune, as it only takes one sponsored clickbait article or one misinformed friend to fall into the trap. New Zealand need not look far for examples of populism – the Advance NZ Party was removed from Facebook in the run-up to the 2020 election for spreading false claims regarding COVID-19 and vaccinations (Newshub, 2020).

Polarisation and echo chambers

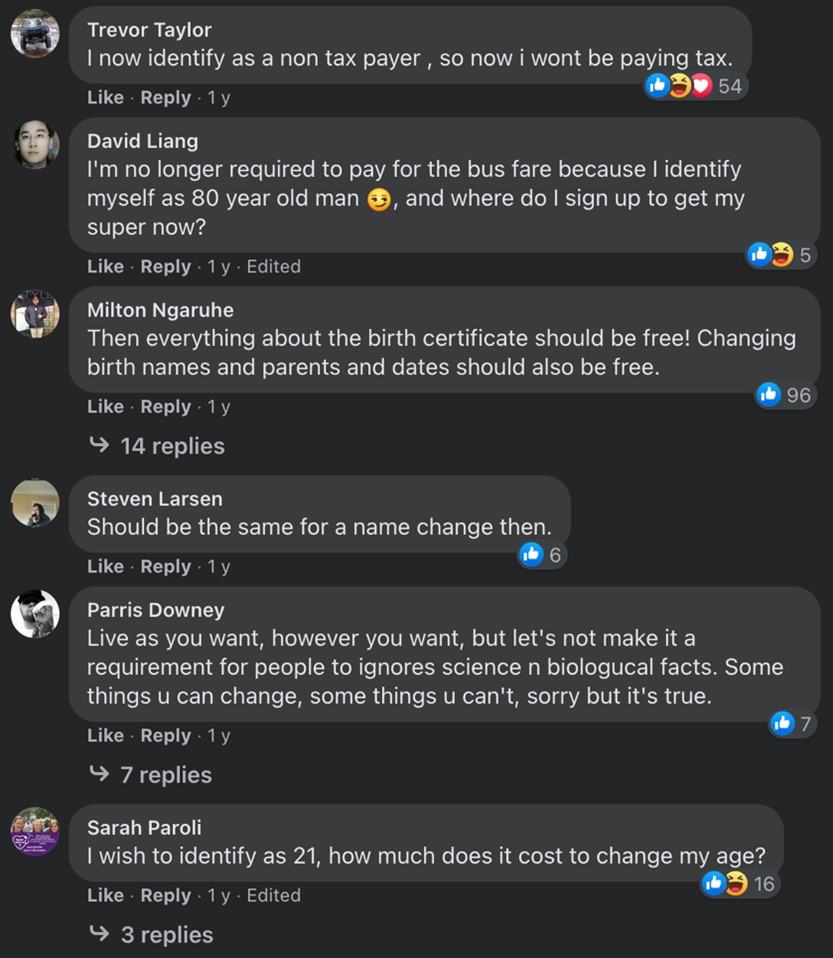

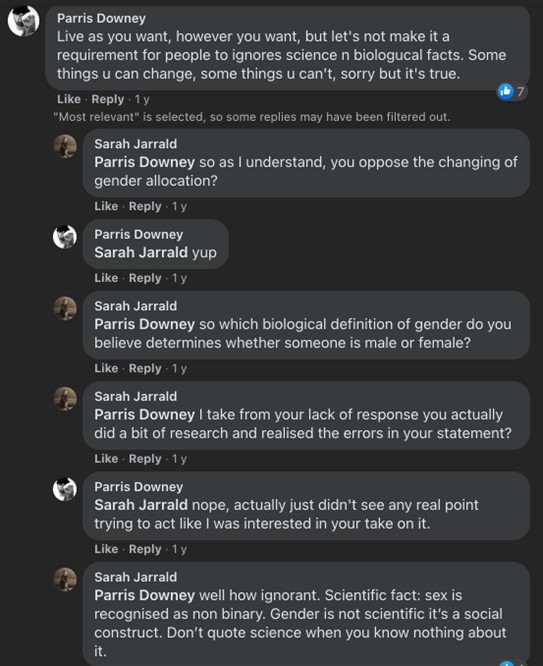

While social media facilitates political discussion, the discussion that occurs is not always positive or beneficial to democracy. In fact, according to Deb et al., social media “has exacerbated political divisions and polarization” (2017, p. 4). Such polarisation can be found in most comment sections of news articles posted on Facebook; for example, Stuff’s link to an article accompanied by the caption “Changing the sex marker on a birth certificate is now free for transgender and non-binary Kiwis” (Stuff, 2019). Figure 3 shows the first comments that appear when sorted by ‘most relevant’, the default setting. These are overwhelmingly conservative - while it is fair to assume there are views expressed in this comment section at the other end of the spectrum as shown by Figure 4, this could partly be caused by the open nature of such posts, which are able to appear in your newsfeed regardless of whether you are following the outlet that posted them due to sponsorship and Facebook’s algorithm.

Figure 3: Top comments on a Stuff article posted on Facebook (Taylor et al., 2019)

Figure 4: Example of divided views in the comments (Downey & Jarrald, 2019)

Polarisation worsens when information systems are not open. They become echo chambers; or in simple terms, ‘group polarisation’, where “like-minded people talk to one another and end up thinking a more extreme version of what they thought before…” (Sunstein, 2018, p. 84). The forming of such groups is destroying the ‘deliberative democracy’ many hoped social media could sustain (Kemp, 2016). Instead of deliberating and collectively seeking ‘the better argument’ as Jürgen Habermas (1989) envisaged, social media has accelerated fragmentation into multiple public spheres where, guided by confirmation bias, each group believes theirs is ‘the better argument’. Although the removal of Advance NZ Party’s Facebook page had a tangible impact on its presence in the unitary public sphere, for the 883 members (as of June 11th 2021) of the "I voted for Advance NZ Political Party" Facebook group, the party’s rhetoric will still be heeded (I voted for Advance NZ Political Party, 2020).

Conclusion

After exploring both positive and negative effects of social media on access to political information through a New Zealand lens - increased political transparency and approachability, greater youth engagement; clickbait, mis/disinformation, and echo chambers - the question remains: does social media have a net positive or negative impact on democracy? I have found that there is certainly a case for either argument. In my opinion, the answer depends on us – we have the responsibility of choosing how to treat the accessibility and connectivity that social media grants us. We need to accept this responsibility at personal, organisational and governmental levels if we wish to harness social media’s capabilities to progress and strengthen democratic principles; otherwise, we risk succumbing to the negative aspects of social media.

References

Ardern, J. [@jacindaardern]. (2021, June 10). Today I was confronted with a very controversial question while visiting the Wattie’s Factory in Hastings. Spaghetti, or Baked Beans? [Image attached] [Status update]. Facebook. Retrieved June 11, 2021 from https://www.facebook.com/jacindaardern/posts/10157938142442441

Deb, A., Donohue, S., & Glaisyer, T. (2017). Is Social Media a Threat to Democracy? The Omidyar Group.

Downey, P., & Jarrald, S. (2019, August 3-4). Changing the sex marker on a birth certificate is now free for transgender and non-binary Kiwis. [Comments on post by @Stuff.co.nz]. Facebook. Retrieved June 11, 2021 from https://www.facebook.com/Stuff.co.nz/posts/10157694276654268

Glasshouse Consulting. (2020). Where Are The Audiences?

Habermas, J. (1989). The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere. Polity Press.

Hacker, K. L., & van Dijk, J. A. G. M. (2000). Introduction and History. In Hacker, K. L., and van Dijk, J. A. G. M. (Eds.), Digital Democracy: Issues of Theory and Practice (pp. 1-9). Sage.

Hayward, J., & Rudd, C. (2006). Media and Political Communication. In Miller, R. (Ed.), New Zealand Government and Politics (4th ed., pp. 479-487). Oxford University Press.

I voted for Advance NZ Political Party. (2020, October 18). [Private group page]. Facebook. Retrieved June 11, 2021 from https://www.facebook.com/groups/1012343349229588

Kemp, G. (2016). Media, Politics and Democracy. In Kemp G., Bahador B., McMillan K., and Rudd C. (Eds.), Politics and the Media (2nd ed., pp. 3-20). Auckland University Press.

Lunt, P., & Livingstone, S. (2013). Media studies’ fascination with the concept of the public sphere: critical reflections and emerging debates. Media, Culture & Society 35(1): 87-96.

McLuhan, M. (1967). The Medium is the Message.

Meyer, T. (2002). Media Democracy: How the Media Colonise Politics. Polity.

Newshub. (2020, October 15). Facebook removes Advance NZ page for ‘repeated’ misinformation about COVID-19. Retrieved June 10, 2021 from https://www.newshub.co.nz/home/politics/2020/10/facebook-removes-advance-nz-page-for-repeated-misinformation-about-covid-19.html

New Zealand Herald. (2017, December 21). Press Council rules on Bitcoin fake ‘stories’. Retrieved June 10, 2021 from https://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/press-council-rules-on-bitcoin-fake-stories/CIZEXLQX3W36WCV2EIN53NVJGU/

Rousseau, J. J. (1762). The Social Contract.

Street, J. (2004). Celebrity Politicians: Popular Culture and Political Representation. British Journal of Politics and International Relations 6 (4): 435-452.

Stuff. [@Stuff.co.nz]. (2019, August 3). Changing the sex marker on a birth certificate is now free for transgender and non-binary Kiwis. [Image attached] [Article link]. Facebook. Retrieved June 11, 2021 from https://www.facebook.com/Stuff.co.nz/posts/10157694276654268

Stuff. (2021, May 29). Transgender students face ‘hoops’ to get into co-ed school, MP says. Retrieved June 11, 2021 from https://www.stuff.co.nz/national/education/125237322/transgender-students-face-hoops-to-get-into-coed-school-mp-says

Sunstein, C. (2018). Is Social Media Good or Bad for Democracy? The SUR File on Internet and Democracy 15 (27): 83-89.

Taylor, T., Liang, D., Ngaruhe, M., Larsen, S., Downey, P., & Paroli, S. (2019, August 3). Changing the sex marker on a birth certificate is now free for transgender and non-binary Kiwis. [Comments on post by @Stuff.co.nz]. Facebook. Retrieved June 11, 2021 from https://www.facebook.com/Stuff.co.nz/posts/10157694276654268

Weedon, J., Nuland, W., and Stamos, A. (2017). Information Operations and Facebook. Facebook. Retrieved June 11, 2021 from https://about.fb.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/facebook-and-information-operations-v1.pdf