The use of te reo Māori in New Zealand English

Originally submitted: October 2020

This is my report for a whole-course project focused on measuring familiarity with te reo Māori usage in New Zealand English and relating that to people's language attitudes.

Introduction

The use of Māori words is perhaps the most salient and unique aspect of New Zealand English. Our project aimed to investigate just how knowledgeable New Zealanders are regarding Māori vocabulary and which factors may have an impact on that knowledge. This report will introduce the project and discuss its results.

Research on the extent and potential growth of Māori in the New Zealand English lexicon has increased substantially since the late 1980s, as social and political changes such as the 1987 Māori Language Act came into play. John Macalister in particular has contributed copiously to this area. His paper “Tracking changes in familiarity with borrowings from te reo Māori” (2008) and its associated research project have formed the basis for this project. While his focus was on predicting growth in the Māori vocabulary of senior secondary school students in the Greater Wellington area, we have altered the methodology in order to get a more representative picture of all New Zealanders.

Using the data collected from our project, I hope to gain an insight on whether language attitudes affect New Zealanders’ knowledge of Māori borrowings, and how that knowledge has changed over time (using an apparent time model). Most New Zealanders are familiar with the ongoing efforts to revitalise Māori and how divisive that topic can be; I am interested to see whether the same applies to the presence of Māori in New Zealand English, seeing as the use of borrowings in one’s native language is arguably more “natural” and “acceptable” than actually learning and speaking Māori.

After a summary of relevant literature, I will turn to our research project by first explaining its methodology, then presenting and discussing the results. Finally, I will provide a conclusion and evaluation of the project.

Literature review

Many efforts have been made to work out the frequency of Māori words in New Zealand English. Macalister (2006: 102) cites Kennedy and Yamakazi’s (1999) and his own (1999) approximation of six Māori words per thousand words. A large proportion of these words are proper nouns, such as place names, which often lack an English equivalent. This means speakers often cannot “choose” to use the Māori word over its English version as they may in other cases, dependent on their language attitudes.

Although the frequency of Māori words may be increasing, especially in the media (Deverson 1991: 18), this is not necessarily related to an increase in familiarity with such vocabulary (Macalister 2006: 102). Gordon and Deverson (1998) settled on an average total Māori vocabulary (minus place names) of 40 to 50 words (cited in Macalister 2006: 119), however Macalister claims the true figure is higher.

Regarding language attitudes towards Māori, it would appear that these are also becoming increasingly positive.i It is suggested the positive trend is a sign that the everyday use of Māori is becoming more accepted (Te Puni Kōkiri 2010: 45). Thompson (1990: 37) cites Leek (1989) as finding that “Pakeha New Zealanders were reasonably well disposed towards Maori, and the extension of its use into new domains, provided they were not expected to learn the language themselves [sic]”. Contrary to this, Te Puni Kōkiri (2010: 38) found the most common response from non-Māori in response to the question “What do you believe you personally should do to support the Māori language?” was “Learn Māori” (24% of non-Māori responses, 40% of Māori responses). An increasing acceptance of Māori is running in parallel with an increase in the number of students studying Māoriii (Ministry of Education n.d.).

In an environment with a growing acceptance and awareness of Māori, it would follow that familiarity with loan words has also been growing over time, and that it has grown most among those with the most positive attitudes towards Māori. This is the hypothesis which I wish to test.

Methodology

Data for this research project has been collected every year since 2018. Each year an online survey is distributed to students in the course [course name redacted] at the University of Canterbury. These students are responsible for further distributing the survey in order to capture as large and as varied an array of participants as possible. Across all three years there is a total of 4051 responses.

Upon beginning the survey, participants are asked to indicate their gender, age range, ethnicity, whether they were born and/or grew up in New Zealand, which island and region they have spent the most time in, whether they have studied and/or can speak Māori, and if they know any other Pasifika languages. They are then asked to position themselves on a five-point Likert scale in relation to the statements “I have a lot of respect for people who can speak Māori fluently” and “Some Māori language education should be compulsory in school for all children”. Following this, the same 50-item multiple-choice questionnaire used in Macalister (2006, 2008) is used to test participants’ knowledge of Māori words.iii

In our version of the survey it was possible to avoid answering questions, but this was not stated to the participants. It was not possible to select more than one answer per question. A correct answer would output a score of one, while an incorrect or empty answer would output zero.

When analysing the cleaned data, the first step was to generate each participant’s total vocabulary score (out of a possible 50) by adding together their scores for each word. I will be using the total vocabulary scores throughout, while focusing on the responses to the two attitude statements when investigating whether language attitudes affect New Zealanders’ knowledge of Māori borrowings, then using age range to investigate how that knowledge has changed over time (plus exploring a possible correlation with te reo studied).iv

Results and discussion

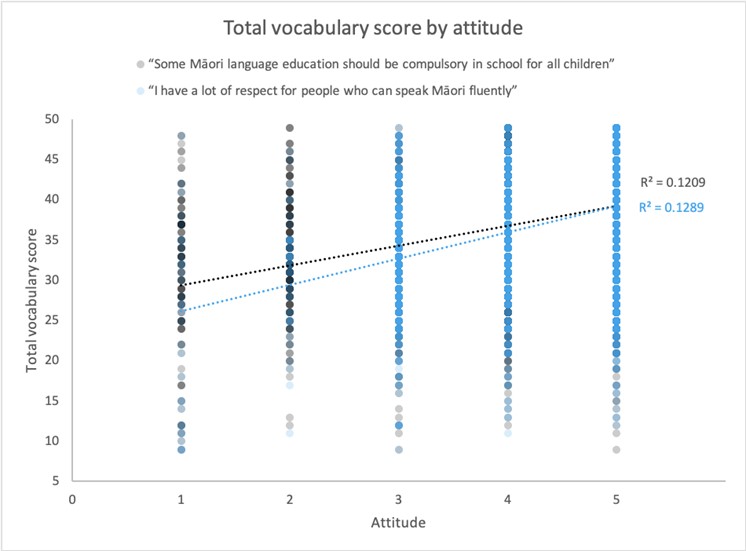

Figure 1: Total vocabulary score by attitude

According to Figure 1, there is a weak positive relationship between the participants’ attitudes towards Māori and their total vocabulary score. The higher they scored themselves on the Likert scale in response to the statements “Some Māori language education should be compulsory in school for all children” and “I have a lot of respect for people who can speak Māori fluently”, the higher their total vocabulary score tended to be. The former statement has a higher R-squared value (0.1289 compared to 0.1209), implying there is a slightly stronger positive association between respect for Māori speakers and familiarity with loan words. From Figure 1 it is apparent that fewer participants scored 1 or 2 on the Likert scale in response to this statement.

The stronger relation between respect and familiarity with loan words could be influenced by those who are fluent or working towards fluency in Māori (and therefore likely to recognise more loan words) understandably holding more respect for fluent Māori speakers. Meanwhile, even people who aren’t fluent (and therefore less likely to recognise loan words) may like the idea of compulsory Māori education, regardless of what level of Māori education (if any) they have been through themselves.

The comparative lack of participants who scored 1 or 2 in response to the statement “I have a lot of respect for people who can speak Māori fluently” could be in part due to the personalness of this statement. Participants may have felt reluctant to come across as “disrespectful” by giving a low score. In comparison, the statement “Some Māori language education should be compulsory in school for all children” is not as loaded and could be easier to disagree with.

Overall, Figure 1 suggests language attitudes could affect knowledge of loan words, with positive attitudes linked to more familiarity with loan words. A similar finding was established by Thompson (1990) by giving participants a cloze exercise with gaps which could be filled with English words or Māori loan words; the participants with more positive attitudes towards Māori were more likely to use loan words.

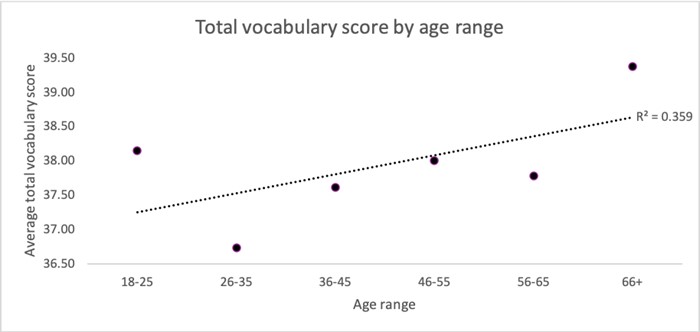

Figure 2: Total vocabulary score by age range

According to Figure 2, there is a positive relationship between participants’ age and their total vocabulary score. While the R-squared value is 0.359, it is interesting to note the data points themselves do not adhere entirely to this trendline; instead, there is a relative peak in the 18-25 age range (38.16 average total vocabulary score), which is only eclipsed by the 66+ age range (39.38 average total vocabulary score).

The peak at the 66+ age range could be due to more positive attitudes among the relatively small sample size (92, compared to an average of 791 across all other age ranges). Upon investigation, it was found that the average score among the 66+ range in response to the compulsory Māori statement was 4.4, compared to the overall average of 4.37; the average score among the 66+ range for the respect for Māori speakers statement was 4.6, compared to the overall average of 4.53. These more-positive-than-average attitudes could have contributed to this age range’s high average total vocabulary score.

The peak at the 18-25 age range could be due to the rapid increase of Māori availability and demand in primary, secondary and tertiary education over the past decades. In 2000 there were 155,628 primary students and 22,218 secondary students receiving some level of Māori education, compared to 171,143 and 30,156 respectively in 2019 (Ministry of Education n.d.). Being more likely than their predecessors to go through Māori education would increase their chances of recognising loan words.

My hypothesis was that this familiarity would be growing with time, yet this apparent time model would suggest the opposite. The remaining positive trend could be due to exposure, as older speakers have presumably built up more exposure to Māori and therefore have a greater proto-lexicon to help identify loan words (Hay, King and Pierrehumbert 2020). I still predict that a rise in Māori education will improve familiarity with loan words over time, so I will now look more closely at the te reo studied variable.

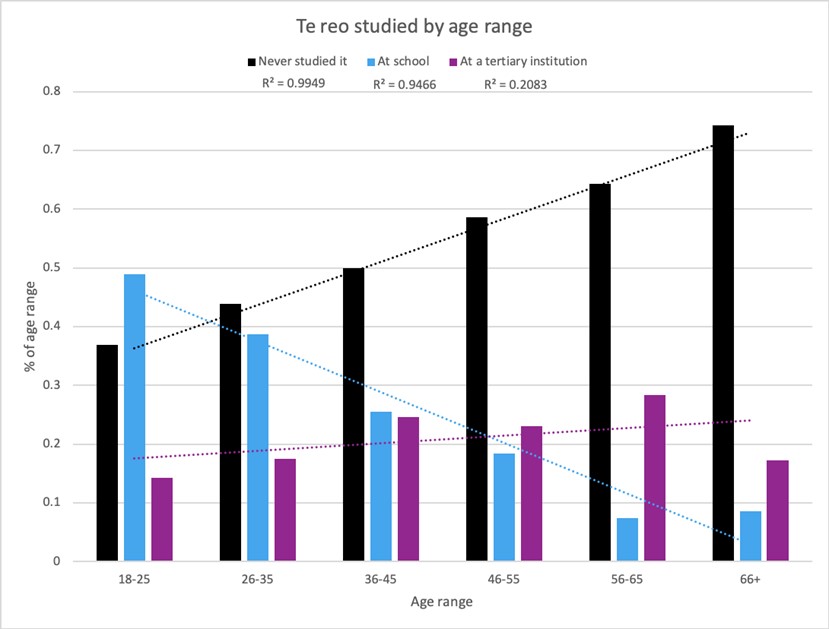

Figure 3: Te reo studied by age range

Figure 3 shows a sharp contrast between the levels of Māori study by participants of different age ranges. There is a strong positive relationship between age and never having studied Māori (R-squared value of 0.9949), indicating that older people are more likely to have not studied it. Meanwhile there is a strong negative relationship between age and having studied Māori at school (R-squared value of 0.9466), suggesting that younger people are more likely to have studied it at school. The relationship between age and tertiary study of Māori is only a weak positive one (R-squared value of 0.2083). This weak relationship could be due to the unrestricted age entry to tertiary courses.

Overall, the relationships shown by Figure 3 show that the ratio of people studying Māori has increased with time. If this trend is stable and the high value of the 18-25 age range in Figure 2 is in fact the beginning of a negative trend between age and vocabulary knowledge, New Zealanders’ knowledge of (and therefore familiarity with) Māori should go up over time. I still predict this will be the case, as active exposure in the form of education ought to be more effective in familiarising oneself with Māori than the passive exposure that all New Zealanders experience, therefore overriding the trend shown in Figure 2.

Conclusion

Our project aimed to investigate just how knowledgeable New Zealanders are regarding Māori vocabulary and which factors may have an impact on that knowledge. I focused on whether language attitudes affect New Zealanders’ knowledge of Māori borrowings, and how that knowledge has changed over time. My expectation was that familiarity with loan words has been growing over time, and that it has grown most among those with the most positive attitudes towards Māori.

I found a weak positive relationship between the participants’ Māori language and their total familiarity with loan words, with a slightly stronger positive association between respect for Māori speakers and familiarity with loan words over agreement with compulsory Māori education. The stronger relation between respect and familiarity with loan words could be influenced by more fluent participants understandably holding more respect for fluent Māori speakers. Meanwhile, the idea of compulsory Māori education may appeal to people regardless of what level of Māori education (if any) they have been through themselves.

I found a positive relationship between participants’ age and their familiarity with loan words, which did not support my hypothesis and could be due to exposure. A peak in the 18-25 age range could be due to the rapid increase of Māori availability and demand in primary, secondary and tertiary education over the past decades, while the peak in the 66+ age range could be due to more positive attitudes among the relatively small sample size for that age range.

After looking at the relationship between age range and te reo studied and finding that the ratio of people studying Māori has clearly increased with time, I hypothesised that the positive relationship between age range and loan word familiarity could be overtaken by this increase, and the peak in the 18-25 age range could signify the beginning of this new trend. My reasoning is that active exposure in the form of education ought to be more effective in familiarising oneself with Māori than the passive exposure that all New Zealanders experience to some degree.

If I were to go through this research project again, I would consider investigating my new hypothesis further by looking at the relationship between level of Māori education and familiarity with loan words compared to the relationship between age range and familiarity with loan words. I may also consider altering the methodology in some areas, for example administering the survey to a set group of participants so that responses are not reliant on people “wanting” to complete the survey of their own will, as this may have been biased towards people with positive attitudes towards Māori. Selecting a representative group of participants would also eliminate the imbalance that was caused by relying on university students to redistribute the survey, as this resulted in a greater proportion of younger people responding. Another possible change could be asking for the definition of Māori words in an open-ended format instead of multiple-choice, to make it harder for participants to guess and provide an inaccurate representation of their actual knowledge.

References

Deverson, T. (1991). New Zealand English lexis: the Maori dimension. English Today 26: 18-25.

Gordon, E. and Deverson, T. (1998). New Zealand English and English in New Zealand. Auckland: New House.

Hay, J., King, J. and Pierrehumbert, J. (2020 - ongoing). Statistical learning with and without a lexicon. Unpublished.

Kennedy, G. and Yamakazi, S. (1999). The influence of Māori on the New Zealand English lexicon. In Kirk, J. (ed.) Corpora Galore: Analyses and Techniques in Describing English. Amsterdam: Rodopi, 33-44

Leek, R. (1989). Attitudes to the Maori language in New Zealand. Paper presented at the 8th New Zealand Linguistics Society Conference: Auckland.

Macalister, J. (1999). Trends in New Zealand English: some observations on the presence of Maori words in the lexicon. New Zealand English Journal 13: 38-49.

Macalister, J. (2006). Of Weka and Waiata: Familiarity with Borrowings from Te Reo Māori. Te Reo 49: 101-124.

Macalister, J. (2008). Tracking changes in familiarity with borrowings from te reo Māori. Te Reo 51: 75-97.

Ministry of Education. (n.d.). Education Counts – Māori Language in Schooling. Retrieved 23/10/20 from https://www.educationcounts.govt.nz/statistics/6040

Te Puni Kōkiri. (2010). 2009 Survey of Attitudes, Values and Beliefs Towards the Māori Language.

Thompson, W. (1990). Attitudes to Māori and the use of Māori lexical items in English. Wellington Working Papers in Linguistics 1: 37-46.

Notes

i In Te Puni Kōkiri’s 2009 survey, it was found that 68% of Māori and 64% of non-Māori respondents agreed that some te reo education should be compulsory for all children (compared to 65% and 56% in 2006), and that 95% of Māori and 87% of non-Māori respondents claimed to have a lot of respect for fluent te reo speakers (compared to 93% and 81% in 2006) (2010: 46).

ii The number of students enrolled in Māori-medium schools went up by 978 between 2018 and 2019, while the number studying Māori in English-medium schools went up by 9,237 (Ministry of Education n.d.).

iii The 50 Māori words (sourced from the New Zealand School Journals, Hansard parliamentary debate archives, and newspapers) are divided into three categories: flora and fauna (FF), 14 words; material culture (MC), 11 words; and social culture (SC), 25 words (Macalister 2006:104). Four options were given as possible definitions for each Māori word; one being the correct answer, plus three of the following:

- The meaning of a similar-sounding Māori word type

- The meaning of a similar-sounding English word type

- An item in a related semantic field

- A randomly selected meaning (Macalister 2006: 105)

iv There were a few things I had to take into consideration while working with the data. Because the semantic categories were not evenly sized, I calculated the percentages of correct words so that the categories could be compared more accurately (although ultimately I did not compare the categories in my results). I converted the te reo studied values to percentages of each age range for the same reason. The responses “at a tertiary institution” and “at university” were combined for the te reo studied values as they were not both consistently available over the years, and I consider them to be equivalent. When working with the attitude to fluency values, two responses had to be removed (and were subsequently removed from all of my figures) as their lack of a response to this question was interfering with the graph outputs.